Mexican Adventure Home Page Travels Page

It is a wintry Monday morning in the middle of March. Snow covers the grounds outside my bedroom and I would now be attending my morning kindergarten class were it not for a union walkout by the Public School “Janitors” (now referred to as “Maintenance Engineers”)

The strike, expected to last perhaps three or more weeks, kept children from attending classes. My parents chose to seize this opportunity to take a three-week vacation. Fortunately the choice was not to be another fishing adventure. Instead of traveling North to some lakes waters, we steered south toward the Mexican border in my fathers new 1947 Rocket 88 Oldsmobile. The car was equipped with an innovative contraption known as “hydromatic Drive” (The first of the automatic transmission cars). This journey afforded me the opportunity to learn of a culture other than that of the neighborhood boundaries I was generally confined to.

Driving what seemed endlessly from our home in Minneapolis Minnesota to just reach the border of Mexico was beautiful and as foreign to the eyes of this five year old as our country of destination was to be. My father loved to drive. My mother hated to ride with him but wished to drive even less. I was enthralled by the scenery. Super thoroughfares not yet available, we made our way along two-way highways. Incessant urging for my father to “slow down”, my mother was forced to rely on the handle attached to her door for safety. She must have felt she would be safer in the grip of that handle should my father misjudge the distance of that next on-coming car, as he came within feet of slamming directly into the front of its bumper before swerving back into his own lane. He must have saved two, maybe three, minutes of time by passing all those cars.

Two days into our journey found us at the Mexican border where some guy stared at me as though I might be some sort of deranged child. Either he didn’t like me or he didn’t like his job. I wasn’t sure which but we soon escaped the border guards and were in the county that my mother had described as being as different as that described by my Chinese friend. Everything looked the same to me. I was told that all would change once we got into Mexico but it didn’t. Same ol’ highway, same ol’ sand, same kind of stuff I saw in Texas.

I was sorely disappointed until we reached the city of Monterrey. Here we visited Barrio Antiguo, or old town. My mother fascinated by the old architecture; cathedrals and such; my father more interested in the restaurants. His idea of a great outing was to find a great place to eat – cheap. I was more inclined to watch the people. They didn’t look different to me. I was told they would look “unusual”. Some looked poor. Many wore funny looking hats. But they looked like people.

While visiting a restaurant, I noticed the biggest difference yet. My parents could not communicate with the waitress. Everyone around us was speaking gibberish. I was reminded of my Chinese friend who had told me that in different countries, people sometimes spoke a different language. This certainly was not English and I was curious about it. My mother apparently learned a few words in the hopes of communicating better. She said “Grah-see-ahs”; my father would repeat “Grass-ee-ass” – which apparently embarrassed my mother.

Not until we reached Taxco and then Mexico City did I have an opportunity to experience what I now know as “culture”. Taxco because of a motel where we stayed that had a number of incredibly colorful parrots throughout its grounds. There I became mortified when I discovered that, as I wandered among the many motel buildings, I lost track of which one held our room. I entered a room that I thought might be ours only to discover suitcases and articles that did not look familiar to me. I quickly left hoping that no one would notice and throw me in a Mexican jail. Here I tried to communicate with maids and other workers. Most spoke no English. Some practiced their limited English but usually smiled and nodded politely during our conversations. I found it interesting that adults could have communication problems as well as children. I also thought, “if I can’t understand them – and they can’t understand me – then it is my fault because I am in their country”. That made sense to me then and it makes sense to me now.

Mexico City was an enlightening experience. Driving through a poor section of the city I saw people living in dwellings I thought were from a time before Jesus. Tattered clothing on adults and sometimes-naked children were sitting outside homes made of a mixture of wood and metal sheets. Some were living in caves along the sides of hills. Women were cooking, children were playing and men were scarce. I could not believe people live like that. I tried to ask my parents why they didn’t have better homes and nicer clothes. My dad said, “Because they are poor”. “Why are they poor?” I asked. “Because they don’t have any money”, said my father. “Why don’t they have money?” said I. I don’t recall the response but I suspect I was told to look at something else. My dad was not a deep thinker.

I was obsessed by these visions of poverty everywhere we went. While I suspect my parents wanted to experience the sights of old forts and churches and shop for Mexican paraphernalia, I fanaticized about how I could make these peoples lives better. My thinking was not very practical. I thought I could share the bedroom my brother and I already shared. It was the sun porch of a one-bedroom apartment back in Minneapolis. I thought we could spare some food. Our cupboards were full of food. I wanted to stop and meet these people. I was told that they did not want to meet me – “they” couldn’t even speak “our” language. I was young, but even at age five I realized that it was “I” who could not speak “their” language.

While my parents wanted to “see” things, I had a desire to help people escape their festering poverty. I thought we could at least give them some money. My father said, “what? Do you think I’m made of money?” I didn’t know what that meant but I suspected it meant “no”.

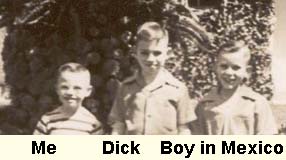

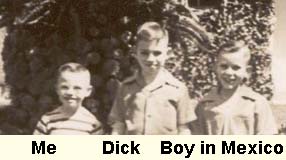

I met a boy, perhaps nine, at an open market. I wasn’t as impressed that he spoke English, as I was that he seemed to speak both English and Spanish flawlessly. The boy helped my brother and me bargain for items we wanted to purchase. I was incredibly impressed that a person could speak more than one language. In later years I struggled to learn the Spanish language but could not seem to master it.

I met a boy, perhaps nine, at an open market. I wasn’t as impressed that he spoke English, as I was that he seemed to speak both English and Spanish flawlessly. The boy helped my brother and me bargain for items we wanted to purchase. I was incredibly impressed that a person could speak more than one language. In later years I struggled to learn the Spanish language but could not seem to master it.

During our time in and around Mexico City my father hired a guide. Jessie was his name. I was curious and asked him many questions. I don’t think he liked inquisitive children for he most often ignored me. Too bad – I could have learned so much more.

I met a boy, perhaps nine, at an open market. I wasn’t as impressed that he spoke English, as I was that he seemed to speak both English and Spanish flawlessly. The boy helped my brother and me bargain for items we wanted to purchase. I was incredibly impressed that a person could speak more than one language. In later years I struggled to learn the Spanish language but could not seem to master it.

I met a boy, perhaps nine, at an open market. I wasn’t as impressed that he spoke English, as I was that he seemed to speak both English and Spanish flawlessly. The boy helped my brother and me bargain for items we wanted to purchase. I was incredibly impressed that a person could speak more than one language. In later years I struggled to learn the Spanish language but could not seem to master it.